Sunday, September 6, 2009

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

In Afghanistan, Let's Keep It Simple

Sunday, September 6, 2009

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

Home and Home

I’ve been told that diplomats and military men remember with nostalgia the first alien lands in which they served, and I suppose this is inevitable; but in my case I look back upon Afghanistan with special affection because it was, in those days, the wildest, weirdest land on earth and to be a young man in Kabul was the essence of adventure.

The city of Kabul, perched at the intersection of caravan trails that had functioned for more than three thousand years, was hemmed in on the west by the Koh-i-Baba range of mountains, nearly seventeen thousand feet high, and on the north by the even greater Hindu Kush, one of the major mountain massifs of Asia. In the winter these powerful ranges were covered with snow, so that one could never forget that he was caught in a kind of bowl whose rim was composed of ice and granite.

Sunday, May 10, 2009

Happy Mother's Day from Kabul!

May 10, 2009 This morning as the car rounded the corner on Street #6, Taimani Watt, Kabul, Afghanistan, the balloon seller was making his way down the road, stopping to let neighborhood children admire his bouquet. I couldn’t help but smile and feel lucky to have this Mother’s Day in Kabul!

May 10, 2009 This morning as the car rounded the corner on Street #6, Taimani Watt, Kabul, Afghanistan, the balloon seller was making his way down the road, stopping to let neighborhood children admire his bouquet. I couldn’t help but smile and feel lucky to have this Mother’s Day in Kabul!Happy Mother’s Day to one and all, near and far, especially to the two who call me Mom!

"I'll have two, please!"

Pure joy!

The balloon seller's bouquet.

Friday, May 8, 2009

Upside Down

Living in Kabul, I am almost half a day ahead of East Coast time, so it was not until I woke up Wednesday morning to 108 email messages that I learned of this tragedy. The subject line on many of the emails read “shooting on campus?” From there, I searched first for a message from my son and then for a message from the university administration. My son’s message sought first to reassure me that he and his roommates were safe. Safe but sad. The university’s message was also reassuring, although it informed parents that the killer was at large. The campus was immediately locked down, students instructed to remain inside their dorms and houses.

I called my son and heard the grief in his voice. He lost a friend to a car accident when they were in high school. I remember then looking at the boys in suits following their friend’s coffin up the center aisle of the church at the memorial service and thinking “boys to men.” Overnight. Boys to men. Such grief seems untimely.

I remember, too, the expressions of pain on the faces of the mother and father and sister who lost their son five years ago. And I thought of the unbearable grief thrust upon the family of this beautiful young Wesleyan student. I thought of the family receiving that phone call. I thought of Michael Roth, the President of Wesleyan University, making that phone call.

For the past two days, parents in the Wesleyan community have reached out to one another through an email list, grieving, comforting, questioning. Being held in the comfort of this community of Wesleyan parents makes me think that there is a lot more love in the world than there is hate. While none of us can claim to understand one family’s grief and loss, we all mourn for this dear girl. We all want to reach out and hold her family and our children close.

There are no easy answers. What could cause such torment in a person’s spirit that he could take a life so easily? What must his family be feeling? Why?

When things go upside down, how long does it take to put them right again?

Saturday, May 2, 2009

Leeda's Speech

At the age of 20, fourth year Afghan law student Leeda has lived through civil unrest, oppression, and Taliban rule. She was forced to flee her home to continue her education. She was told she was a second class citizen. Hers was the best revenge: she refused to abandon her dreams.

On March 11, I had the privilege of hearing Leeda address an audience of her law school colleagues and professors. Her words capture the anguish of life for Afghan women under the Taliban and the hope for renewal that beats in the heart of every Afghan woman. Leeda points the way into the future for thousands of young Afghan women who dare to dream.

Leeda’s speech

March 11, 2009

Pretend that you woke up in the morning and found yourself crying, bound by time and change. You can’t walk or talk or even breathe easy. That’s the story of every Afghan woman.

There are three kinds of women.

One woman doesn’t feel the change anymore.

One has accepted the change as her reality, who says this is how my life should be, who accepts it the way it is.

The third is the one who struggles for freedom, who wants change on her terms.

I am the third kind.

I was born into a family where I learned that there wasn’t any difference between me and my brothers. That I could do anything. That I had the same abilities as a boy.

I was a running champion at school. No boy could outrun me. I ran fast and I was very confident. I did everything a boy did.

Then schools were closed and I had to sit at home because of the Taliban. For basic education, my family had to leave everything behind. We had to leave our country for Pakistan so I could study.

As I grew up, I realized that I was treated differently from my brothers. I was treated differently from my classmates. I was treated differently from my playmates, the boys. I was treated as a second sex.

When I walked, someone would tell me, ‘Walk like this.’ When I talked, someone would tell me, ‘Talk like this.’ I could not smile or laugh because it was not appropriate for a girl. I could not look into people’s eyes. As a girl, you should never look into people’s eyes, especially a man.

I changed from a smiling girl, a happy girl, into someone who would not look into people’s eyes, who would not try to get out of the house, who hated people, especially men, because they had all the opportunities. I looked at men and I looked at boys and they were free. They walked about freely and I could not, so I hated them.

Then I read an article by Simone de Beauvoir. She said “A woman is not born a woman, a woman is made a woman.”

That sentence made me buy her book, The Second Sex, and read it. That book changed my life. It taught me that I was not the only woman in the world that feels like I do. That I am not alone anymore. That there have been and there are women in the world who feel like me, who are like me.

I don’t feel alone anymore. The Second Sex changed my life.

And now I stand here in front of you looking into your eyes and saying that a woman is not the second sex. I am not the second sex.

Friday, April 24, 2009

Leaving Kabul

Some days the sensory overload knocks me out. Body odor, sewage, garbage, goats, meat, even the soot smells. I hold my breath and then I exhale. I don’t want to be one of those silly people who blanch at the slightest discomfort. I practice mindfulness. There is dust everywhere in Kabul. You can measure the passage of time in the layers of dust.

Much of the time, something here doesn’t work. Satellite TV flickers in and out. Channels switch, so what was once the BBC Lifestyle Channel is now the Peace Channel. Bollywood rules on the air waves. The generator flips on and off like clockwork every day at 4:00 PM. One stop light in Kabul City works from time to time, if you define “working” as maintaining a steady red or green light for 24 hours straight. Showerheads, made in China, work for a time and then they inexplicably explode, hurtling projectile parts in the direction of the bather.

The contrasts stack up: the Safi Landmark Hotel stands resplendent in the Shar-i-Naw district of Kabul, a glass and steel monument to 21st century form and function. The mud houses scaling the hillsides surrounding Kabul tenaciously cling to their dirt foundations. How do the owners get the building materials up those precipices, I wonder every time I look out my window?

Donkey carts cut in front of busses offering “Special for Tourists.” Cars dare each other to the brink, honk, and get on with it. School girls in clusters of a dozen or more, dressed identically in black suits and white chador, walk together giggling and holding hands. The children of Street #6 line up at the well to pump water to bring home. I wonder if they know that they live in the Afghanistan we hear about in U.S. media.

Three months is chump change in Afghanistan. Just enough time to pull back the veil and catch a glimpse of the antiquity that seeps into every corner of Afghan culture and holds this country hostage to a past century. Women in pale, dusty blue burkas shuffle through the streets, heads bowed low. Men in turbans, pakols, karakols (Karzai caps), plaid scarves, salwar kamiz. But then, just when you think you’re stuck in the last century, there are young women in tight jeans, sandals showcasing painted toenails, leather jackets, and head scarves, giving the lie to the burka. Men in Armani suits and Rolex watches straight off the cover of GQ.

Kabul’s bridal shops feature Anglo mannequins that stare off into the far horizon as if mortified to be caught in the 1950s style bridesmaid dresses they are hawking. In the Fancy Wedding Store, they are decked out in heavy satin floor length gowns in dark colors with intricate beading. Most of the mannequins lack complete arms, stopping at the elbows.

I have sunk roots here, but I have gotten tired. I have so much more than I need, while my Afghan friends struggle against such hardship, whether poverty, oppression, or violence. I am not courageous, nor brave compared to the Afghan women who put their lives on the line two weeks ago to protest a law that diminishes women. My simple acts of activism pale in comparison to young Afghan women who stood shoulder to shoulder to reject the notion that women should have to seek permission from their husbands when they want to leave the house, that women should have to “preen” at the whim of their husbands, that women should have to submit to sex on demand by their husbands. These young women stood up to the stones thrown at them and to the chants of “whores” issued by men and women alike who turned out in huge numbers to put the protestors on notice that they had better go home and submit in silence.

How am I going to leave my Afghan home? Who will tell me every morning that “you have beautiful eyes, Mum?” Who will put a dish of sweets outside my office before I arrive? Bring me hot tea? Serve me rice and Nan and fresh fruit at lunch? And who, when I thank them for all this abundance, will respond, “Why not, Miss?” which I figure is the first English phrase most of my Afghan colleagues have learned in the English course they are offered at our office. “Why not?”

These days, I dream of hugging my children. We have never been apart for this long. My beautiful Louisa who cares for her charges as a kind hearted, brilliant social worker, and on top of that worries that I am not safe, especially after hearing on the Today Show that Kabul is ‘the most dangerous city in the world today,’ who always makes sure her Ma and her brother are safe and sound. My handsome Alex whose creative passion is bursting into bloom, who quietly but surely cultivates extraordinary ideas from seed to film, who unfailingly loves his sister and his mother, who worries in his own way. I ache to hug them.

But it will be hard to leave Kabul. In some small ways – and this will sound grandiose, but I don’t know how else to say it – I see myself as a surrogate for my country. I was here the day Barack Obama was sworn in as President. That was the day my Afghan friends asked me if Barack Obama would help Afghanistan, and listed all that needs doing: security, poverty, infrastructure, employment, education, women’s rights. “Yes,” I told them, just short of a promise, “Barack Obama wants to help Afghanistan.” And I believe he does. But I also see that the proposition is enormous. I have toiled in these fields for too short a time.

Monday, April 6, 2009

A Child's Smile

Thursday, April 2, 2009

'Worse than the Taliban'

Afghan women struggle to emerge from the long shadow cast by decades of Soviet occupation and Taliban repression. They chafe at the restraints of a culture that dictates their behavior and relegates them to second-class status. Many brave Afghan women have taken up the fight on behalf of their Afghan sisters. Theirs is a Sisyphean battle, doomed to repeat itself down the generations. The optimist in me says Afghan women can prevail. The skeptic in me says not without blood, sweat, and tears. The cynic in me says the obstacles are too great. My money is on the skeptic.

The news story below deals a vicious blow to the hope of equal rights for Afghan women. I understand that particulars of the law signed by President Karzai are especially galling in their detail and implications for the future of Afghan women.

The Guardian ~~ London ~~ Tuesday March 31, 2009

'Worse than the Taliban' - new law rolls back rights for Afghan women

Jon Boone in Kabul

.JPG) Hamid Karzai has been accused of trying to win votes in Afghanistan's presidential election by backing a law the UN says legalises rape within marriage and bans wives from stepping outside their homes without their husbands' permission. The Afghan president signed the law earlier this month, despite condemnation by human rights activists and some MPs that it flouts the constitution's equal rights provisions.

Hamid Karzai has been accused of trying to win votes in Afghanistan's presidential election by backing a law the UN says legalises rape within marriage and bans wives from stepping outside their homes without their husbands' permission. The Afghan president signed the law earlier this month, despite condemnation by human rights activists and some MPs that it flouts the constitution's equal rights provisions.The final document has not been published, but the law is believed to contain articles that rule women cannot leave the house without their husbands' permission, that they can only seek work, education or visit the doctor with their husbands' permission, and that they cannot refuse their husband sex. A briefing document prepared by the United Nations Development Fund for Women also warns that the law grants custody of children to fathers and grandfathers only.

Karzai's spokesman declined to comment on the new law.

Monday, March 23, 2009

The Boys Who Live on Street #6

Monday, March 9, 2009

Greetings from Kabul

My mother was the only child of John and Lorraine Templeton. My great-uncle, Dink Templeton, a 1920 Olympics gold medalist with the U.S. rugby team, and his wife, Cathy, had two daughters: Jean and Robin (Binnie). Between them, Jean and Binnie have 8 children. Those 8 children, including Robin and Marti, Jean’s daughters, are my second cousins.

It has only been later in life that Robin and Marti and I have discovered each other as cousins and as friends, and I count myself lucky to have these two amazing women in my life. Both are artists. Robin’s medium is the written word. She is a novelist and a poet and a teacher. Marti paints extraordinary canvasses, filled with vibrant worldly images, both material and ethereal.

Last week, Robin was selected to read an original poem at the 27th annual Santa Cruz [California] Celebration of the Muse. I asked her if I could share the poem she wrote and she agreed. Her writing reminds me of the power of words to move and inspire.

With love and thanks, Robin, I share your poem here.

(for Ann and her Afghan Sisters- tashakor!)

Greetings from Kabul!

I AM FINE! my cousin Ann writes.

She is working in Afghanistan,

trying to bring some order to the country.

I write progress reports, she says.

Shuttered in a pink guest house,

built by a drug lord, with Persian rugs,

marble floors, she’s grateful for the Afghan cook

who prepares American cuisine,

for the private bathroom with a hot shower.

I can’t go outside on foot, at all.

Every Friday, I go to town

in an armored truck

with a driver and bodyguard.

Children sell gum in the streets.

Donkey carts mix with taxis.

Women in burkas beg on the corners,

mingle with prostitutes, also in burkas,

their fingernails colored-coded.

I express my fears reluctantly.

She knows what I’m thinking:

Rocket attacks, kidnap, rape, beheadings.

I’m not afraid.

Wherever you live,

circumstances quickly

become the norm.

She and I share a matriarchal bloodline

have sought the edge most of our lives.

Lately, mine blunts as hers sharpens,

a bone-handled paradigm.

She asks for photographs of my three grandsons,

to hang in office, to remind her of home.

I imagine their faces adorning her wall,

worry what passersby will think of these fair, All-American boys.

She insists we only hear the bad news.

I’m trying to raise money

for my friend Humaira Haqmal.

who drives the Taliban-controlled district

to Kabul every day to teach at the law school.

Humaira works with the Afghan Sisters Movement.

I stumble on spelling Afghan.

The “h” unsettles me.

Is this the first time I’ve written the word?

I am going to raise money for Humaira, my cousin vows.

I am going to write about these Afghan women.

Humaira, Humaira, of an arranged marriage,

who is raising six children,

has registered 600 women

for the August election.

August election? Where have I been?

My cousin is keen

on the incoming 17,000 American troops.

I remember her as a pacifist,

imagine the juxtaposition

of her carefully placed head scarf

and the carefully placed body guard.

I love the Afghan people.

I love the city of Kabul.

Soft rain taps the roof.

I email Ann at midnight

from my warm bed,

my husband snoring softly beside me.

I think of her friend Humaira,

stopped at a roadblock,

wonder what she is wearing,

how she speaks to the soldiers.

Tashakor

Thank you

--Robin Somers March 7, 2009

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Kabul, the most remote of capitals

Friday, February 27, 2009

Humaira Haqmal and the Afghan Sisters Movement

February 27, 2009 One of my greatest pleasures since I have been in Kabul has been getting to know a group of women law professors who have been in Kabul since January polishing their English language skills. One of my colleagues asked me if I would be willing to spend a few mornings a week with them speaking in English. I was delighted. (Left to right in the photo: Humaira Haqmal, Nadia Noorzi, Anargul Mansouri, Noor Jahan Xousfuzai, and Nadia Alkan.

February 27, 2009 One of my greatest pleasures since I have been in Kabul has been getting to know a group of women law professors who have been in Kabul since January polishing their English language skills. One of my colleagues asked me if I would be willing to spend a few mornings a week with them speaking in English. I was delighted. (Left to right in the photo: Humaira Haqmal, Nadia Noorzi, Anargul Mansouri, Noor Jahan Xousfuzai, and Nadia Alkan.Over the weeks, a deep bond of friendship has formed between us. They have told me what it was like to live under the Taliban when women were not allowed out of their homes. One of them said the best thing about the Taliban was that women had more babies because they could not leave home! They have explained the benefits of arranged marriages. With one exception, all believe this system works. And, indeed, “arranged” does not mean that their parents round up a stranger. It means they likely marry the son of family friends, someone they have known at a distance. They have told me that they are paid the same as their male law professor counterparts. They love their work and they love their families.

At one of our morning gatherings, Humaira Haqmal, a Professor at Kabul University’s Faculty of Law and Political Science, wife and mother of 6 children, and President of the Afghan Sisters Movement, mentioned in a quiet voice that she would be traveling to Washington, DC in March to receive the Jeane Kirkpatrick Award from the International Republican Institute for her work to support and restore the rights of Afghan women. (Humaira Haqmal is on the left in the photo; Nadia Noorzi is on the right.)

At one of our morning gatherings, Humaira Haqmal, a Professor at Kabul University’s Faculty of Law and Political Science, wife and mother of 6 children, and President of the Afghan Sisters Movement, mentioned in a quiet voice that she would be traveling to Washington, DC in March to receive the Jeane Kirkpatrick Award from the International Republican Institute for her work to support and restore the rights of Afghan women. (Humaira Haqmal is on the left in the photo; Nadia Noorzi is on the right.)The Afghan Sisters Movement is a nonprofit organization which encourages Afghan women to find their political voices, to participate in political activities, and to vote. Humaira is a tireless and fearless advocate for women’s rights and human rights. To date, she has registered over 600 women to vote in the August 2009 presidential election. She is one of many Afghan women who grew up under Soviet occupation and then under the Taliban regime and is committed to ensuring that Afghan women play a vital role in Afghan society.

Coming so soon after my experience in the Obama campaign, I have been fascinated to learn more about Humaira’s work. This is what I will carry away with me when I return home: the courage and determination of Afghan women to claim their place in society. It’s a tall order in a culture where custom and tradition still label women as second-class citizens. My money is on Humaira and the Afghan Sisters Movement.

Food in Kabul

February 27, 2009 I have not had a bad meal since I arrived in Kabul. Ali, the 23-year old Afghan cook at the Guest House is a whiz at preparing anything. Roast Beef and Yorkshire Pudding. Fried Chicken. Chili. Mu Shu Pork. Tiramisu. Cannoli. Even a King Cake for Mardi Gras. And everywhere I go in Kabul, food is in sight, whether it's the freshly slaughtered lamb haunches hanging from a rack on Butcher Street, the street vendor carts that offer a deep fried turnover called bowlane (phonetically: baloney) filled with leeks and potatoes, or a shop steaming with the fragrance of newly fried jelAbe, a waffle like sweet made of sugar, honey, and flour. On the Khair Khana Road leading into Kabul is an open air market that stretches for at least a mile, its produce stands featuring artfully arranged cauliflower, radishes, leeks, onions, oranges, lemons, and potatoes. There you can also find fish nailed to boards, ready to sell, as well as cooking oil, Nan, and Snickers bars. And everywhere food is found, there are children eager to have their photos taken.

February 27, 2009 I have not had a bad meal since I arrived in Kabul. Ali, the 23-year old Afghan cook at the Guest House is a whiz at preparing anything. Roast Beef and Yorkshire Pudding. Fried Chicken. Chili. Mu Shu Pork. Tiramisu. Cannoli. Even a King Cake for Mardi Gras. And everywhere I go in Kabul, food is in sight, whether it's the freshly slaughtered lamb haunches hanging from a rack on Butcher Street, the street vendor carts that offer a deep fried turnover called bowlane (phonetically: baloney) filled with leeks and potatoes, or a shop steaming with the fragrance of newly fried jelAbe, a waffle like sweet made of sugar, honey, and flour. On the Khair Khana Road leading into Kabul is an open air market that stretches for at least a mile, its produce stands featuring artfully arranged cauliflower, radishes, leeks, onions, oranges, lemons, and potatoes. There you can also find fish nailed to boards, ready to sell, as well as cooking oil, Nan, and Snickers bars. And everywhere food is found, there are children eager to have their photos taken.

Vendor preparing jelabe. My friend and driver, Sayed Mohammed, took me to this shop in the Khair Khana neighborhood.

.

Open air market on Khair Khana Road.

Afghan child selling chicken pieces at the open air market.

Fish on a stick!

This little piggy went to market!

Driving in Kabul

February 27, 2009 Cars. SUVs. Bicycles. Donkey carts. Goats. Police vehicles. Busses. Taxis. Transports. Trucks. Green license plates (INGOs). Blue license plates (United Nations). White license plates(resident of Kabul). No license plates. All share the city streets of Kabul in a rhythmic traffic dance that miraculously seems to work.

February 27, 2009 Cars. SUVs. Bicycles. Donkey carts. Goats. Police vehicles. Busses. Taxis. Transports. Trucks. Green license plates (INGOs). Blue license plates (United Nations). White license plates(resident of Kabul). No license plates. All share the city streets of Kabul in a rhythmic traffic dance that miraculously seems to work.Driving in Kabul is a test of will. It is a good thing that alcohol is not sold or consumed in this Muslim country so driving under the influence does not come into play. Since I am only driven and do not drive myself in Kabul, I can only imagine what it must be like to be in the driver’s seat. The word “intrepid” applies. Split-second timing and instant reflexes are a must.

Kabul has no stop lights. Well, that’s not exactly the truth. It has ONE stop light and it either runs red or green for 24 hours at a stretch. There are stop signs on the side streets that lead into the main arteries, but they are more decoration than deterrent.

There are traffic circles scattered throughout Kabul, each with a diminutive rotary in the middle that looks like the children’s merry-go-rounds found in the public parks of the 1950s. At every rotary, a policeman swings a cautionary Stop sign the size of a ping pong paddle at merging traffic. Herding cats, for the most part. The policeman with the ping pong paddle is merely street furniture. No one pays much attention.

But maybe not in Kabul!

At the moment of near-engagement, there is a subtle exchange of eye signals between drivers. The oncoming driver stops within inches of the side street encroacher. Looks go back and forth. The encroacher sends a signal to the oncomer that somehow salvages the oncomer’s pride and allows the encroacher to proceed into traffic. The term “road rage” has no equivalent in Dari or Pashto!

Once launched on a main street, a more sophisticated skill set is required. Driving on Kabul’s main streets is a game of Thread the Needle as vehicles, pedestrians, and animals vie for space on a two-lane two-way street with all of the above in play: donkey carts, children and women in burkas begging in the street, SUVs, taxis, bicycles, rickshaws, transports, and trucks. Surprisingly, a car horn is a weapon of last resort.

Driving in Kabul is simple. Proceed at all speed, never mind direction. Stake your claim. Keep going. You will encounter vehicles hastily parked curbside, pedestrians darting in front of your path, the occasional herd of goats making their way through the city. Accelerate, don’t negotiate.

I have never seen one of my drivers lose ground. Never. In the two months I have been in Kabul, I have seen only two automobile accidents in the city streets. This is improbable, to say the least. Every trip by car is a thrill ride. Bumper cars. Chicken. I Double Dare Ya!

It seems to work. When I complimented my driver, Sayed Mohammed, on his masterful driving skills, he said, “It is easy. I was a tank driver in the Afghan National Army. Driving this car is like driving a bicycle.”

Thursday, February 12, 2009

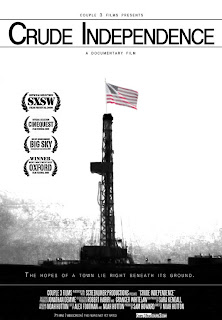

Crude Independence

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

Head Scarves

So it was this morning that I decided to pull out my "good" scarf, the lavender silk scarf I bought to wear to the Inaugural Ball at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul. I swirled the silk scarf around my neck and then decided to cover my head with a second scarf -- second best, at that.

When I arrived at the Safi Landmark Hotel in Kabul for my get together with my friends , they admired the lavender silk scarf. "Very pretty, like your eyes," Nadia complimented me.

And then, halfway through our time together, Anargul, seated across from me, tilted her head slightly and smiled at me. "Why do you wear two scarves?" she asked. Clutching the back-up scarf, I said, "I don't know. Shall I take it off?"

"Now," Noor Jahan said, "cover the lavender scarf over your head."

And so I did, to a chorus of "Oooohs."

I had to come all the way to Kabul to finally make a fashion statement!

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Trouble the Water Nominated for Academy Award

TROUBLE THE WATER

Tia Lessin and Carl DealACADEMY AWARDS HISTORY

These are the first Academy Award nominations for Tia Lessin and Carl Deal.

FILM SYNOPSIS

As the drama of Hurricane Katrina unfolded, New Orleans resident Kimberly Roberts recorded the chaos and devastation of her own experience on videotape. Her footage forms the heart of this portrait of Roberts's long journey with her husband, from the early days of the storm to their subsequent evacuation, resettlement in Memphis, and eventual return to the decimated city.Friday, February 6, 2009

Afghanistan: Guns or Butter?

Insecurity is the dark cloud hanging over Afghanistan, and until some semblance of security is achieved, it seems unlikely that the other pieces such as paved streets, reliable electricity, clean water, new schools, and meaningful employment that pays a living wage will fall into place.

In the time I have been in Afghanistan, I have heard Afghan bodyguards, co-workers, drivers, judges, lawyers, and law professors speak about the state of Afghanistan. There is universal agreement that Afghanistan needs help. But what is needed to restore the basics of life, not to mention human rights and the rule of law? Who can help Afghanistan? Who will help Afghanistan? Is Afghanistan a failed state?

Every Afghan I have spoken with has expressed high hopes for the presidency of Barack Obama. They believe as I do that he is an agent of hope and renewal who can fix what has broken so badly through the past decades of Soviet occupation, Taliban rule, and civil strife. But where to start?

I have had this conversation with many of my Afghan friends. Invariably, they lead with a statement on insecurity. Afghanistan is a dangerous country. Even ordinary Afghans – never mind ex-pats and foreign workers – dare not walk on the streets of Kabul for fear of kidnapping. The cost of living is high and so is unemployment. Municipal services are unreliable: roads remain unpaved, Kabul does not have dependable electricity. Girls go uneducated in provinces outside of Kabul.

The discussion on insecurity leads to a question: “What do you think of President Karzai?” Here follows an informal referendum on President Hamid Karzai: he is weak, he favors his Pashtun tribe, his brother is a drug dealer, he has allowed corruption at the highest levels of his government. Many Afghans hope that a new president will be elected in this August's election and that a new administration will turn things around. But no one seems to know who the new president might be.

The cycle is clear: insecurity breeds corruption, corruption fosters poverty, poverty robs infrastructure, depleted infrastructure deprives Afghans, deprivation breeds insecurity.

One has only to drive through the upscale neighborhoods where houses the size of cruise ships bear witness to the greed and graft that Afghans claim have robbed them of a decent quality of life. Adorned with elaborate mosaic tile designs and painted in pastel pinks, greens, and yellows, many of these houses were acquired at bargain basement prices.

A January 2, 2009 New York Times article, “Bribes Corrode Afghans’ Trust in Government,” describes these upscale, oversize houses as “poppy houses,” suggesting that they are paid for by drug trafficking. “Nowhere is the scent of corruption so strong as in the Kabul neighborhood of Sherpur,” the article states. “Before 2001, [Sherpur] was a vacant patch of hillside that overlooked the stately neighborhood of Wazir Akbar Khan. Today it is the wealthiest enclave in the country, with gaudy, grandiose mansions….” The article goes on to say that “…the plots of land on which the mansions of Sherpur stand were doled out early in the Karzai administration for prices that were a tiny fraction of what they were worth.”

“Inexplicable Wealth of Afghan Elite Sows Bitterness,” a January 12, 2009 Washington Post article, describes “Children with pinched faces beg[ging] near the mansions of a tiny elite enriched by foreign aid and official corruption.” The article continues: “It is difficult to prove, but universally believed here, that much of this new wealth is ill-gotten. There are endless tales of official corruption, illegal drug trafficking, cargo smuggling and personal pocketing of international aid funds that have created boom industries in construction, luxury imports, security and high tech communications.”

Against these odds, every day Afghans pray for an answer to their country’s huge needs. What to do?

Former U.S. Senator George McGovern proposed in a January 22, 2009 Washington Post op-ed piece that rather than “try[ing]to put Afghanistan aright with the U.S. military…” President Obama instead call a “five-year time-out on war….” McGovern suggests that “during that interval, we could work with the U.N. World Food Program, plus the overseas arms of the churches, synagogues, mosques and other volunteer agencies to provide a nutritious lunch every day for every school-age child in Afghanistan and other poor countries.”

Guns or butter? Senator McGovern chooses butter -- "food in the stomachs of hungry kids.” My Quaker faith tugs at me. I can imagine what a nutritious lunch would mean to a hungry Afghan child. And there are too many hungry children on the streets of Kabul. But then I return to the insecurity issue, and I wonder what difference a full stomach makes if you can’t walk on the streets of Kabul?

The Best Things About Kabul

The greeting that meets me every morning when Shah Mahmood drives me to work: Roz-e khush, “have a good day.” Literally, “have a rosy day.”

Moroyhar kanar, or chAklEtA, hard butterscotch candies which the kitchen staff set out in small glass bowls every morning and place in each office in the compound where I work. The hard shell of the candy melts and gives way to a creamy caramel.

Nan, the best bread I have ever eaten. A loaf of Nan, a two foot long flat bread, can be bought at one of the dozens of street bakeries that dot Kabul’s commercial and residential neighborhoods. Indeed, Nan bakeries may be the Starbuck’s of Kabul, that is how close together they are found. Nan is baked on a blazing charcoal grill and sold hot. Breakfast, lunch, dinner, I never get tired of it.

Nan, the best bread I have ever eaten. A loaf of Nan, a two foot long flat bread, can be bought at one of the dozens of street bakeries that dot Kabul’s commercial and residential neighborhoods. Indeed, Nan bakeries may be the Starbuck’s of Kabul, that is how close together they are found. Nan is baked on a blazing charcoal grill and sold hot. Breakfast, lunch, dinner, I never get tired of it.The BGs as our bodyguards are known affectionately watch over all of us who live in the Guest House and work on the Rule of Law Project 24/7. There are 8 BGs, all young Afghan men dressed in natty royal blue blazers and packing heat! My friend and BG, Farid, i

Meena, Salima, Modera, Kamila, Modera, and Razia, my young Afghan colleagues. Salima translates legal publications from Dari to English. She learned English as a child and in her free time teaches young Afghan girls English and math because, as she told me, she was lucky to have a family that encouraged her to get an education and many Afghan gi

Friday, January 23, 2009

Chicken Street

After brunch – Fridays we have brunch at 10 AM in the Guest House – of sausage and the most amazing soufflé-like pancake, I went off to Chicken Street with my friend, Belquis.

I had heard about Chicken Street before I came to Kabul. Carpets, furniture, tapestries, hookas, Karzai hats, chapans (vibrant colored Karzai knee-length jackets), lapis lazuli. You name it, Chicken Street has it.

Today was a lark for several reasons, the most exciting of which is that my friend and I were out together in Kabul without a bodyguard. (Shhhhhh!) We were in a safe area and we were in and out of shops. And we had a phalanx of 7-and 8-year old boys tagging along behind and in front of us, beseeching us to buy chewing gum, offering to carry our packages, and finally determining that they were our bodyguards. At one point, my friend noticed that we were the only women on the street.

We made our way in and out of the most extraordinary shops, each one a warren of small rooms offering feasts for the eyes. Carpets stacked floor to ceiling. Tapestries, silks and wool. Kilim saddlebags for camels. Karzai hats made of lambs wool. Karzai jackets --- chapans – of elegant green and purple fabric. (To be worn, I have it on good authority, with arms in sleeves for informal occasions and draped over the shoulders for formal occasions.) Carved walnut chairs, divans, tables, bed frames. (My friend, Belquis, is trying out one of the beautiful carved chairs in the photograph above.) Lapis lazuli carvings, rings, bracelets, and necklaces. Handblown glass in the most exquisite pale aqua.

All this and the small boys were still escorting us, waiting patiently as we entered yet another store, hoping against hope that we would acknowledge their patience with some form of material reward! We relented and purchased chocolate bars. The boys accepted them with smiles and continued to tag along af

Every shop keeper in every shop we visited offered us tea and sweets and led us up stairs to upper levels where carpets and saddlebags and chairs and tables and wall hangings are kept. We are invited to select items and pay now or pay next time we come back. Afghans give new meaning to the word “hospitality” by their words and deeds.

The colors, textures, carvings, finishes, threads, and patterns dazzle the eye. A

The sun was still high in the sky at 2:00 PM when we returned to the Guest House. I was still feeling the freedom of walking down Chicken Street with my friend, not a care in the world other than a growing pack of young boys eager to please, hoping for baksheesh.

Tonight, I went to the Gandamack for dinner with my new friend, Liz, a beautiful Australian woman who has been here for several months and will be leaving on Monday to return to her home in Spain. This is the third restaurant I have been to since I’ve been in Kabul, and the drill is the same with each one. The restaurants we are allowed to go to are the “double door” restaurants. One enters from an institutional grilled and locked door streetside and crosses a dirt courtyard into a set of double doors. The first door is metal and it is locked. Liz has been there before so she knows to knock. We are viewed through a peephole and we pass muster. We are allowed into a tiny holding stall while we are either viewed again – or in the case of other restaurants, searched for firearms – and then the second door opens and we cross another courtyard and enter what is one of the most beautiful restaurants I have ever seen. White linen tablecloths, sterling flatware, bone china. Candlelight and wine glasses! Boo-yah! The menu offers Boston Climb Chowder and Trout Squeegey Style. (Don’t ask; I didn’t!) Liz has grilled chicken breast and I have Spinach Lasagna. The dinner is delicious and the conversation is wonderful. What a great day!

Every day I wish my children were here with me. I make mental notes to tell them about something I saw, heard, ate, even imagined. How to telegraph the colors, sounds, sights, smells, and tastes? This is too much experience for one person.